I.

Before Marc Andreessen was the bald-headed titan of Venture Capital, he was the founder of Netscape, one of the earliest internet startups. Founded in 1994, Netscape offered the first commercial web browser, ushering the internet from a project mostly used by the government and academics to a mainstream phenomenon. In the process, Netscape invented JavaScript (currently the most popular programming language in the world) and helped guide the early development of HTML and CSS. However, along the way Netscape committed what Andreessen now refers to as the internet’s “original sin”:

So let's say hypothetically you wanted to have an online newspaper [and] you wanted to read an article in that paper and maybe you wanted to have an economic relationship where you were paying for the information…one would think it was the most obvious thing to do to build into the browser the ability to spend money, but you may have noticed that didn’t happen.

…So I think the original sin was that we couldn’t actually build economics, which is to say money, at the core of the internet.

In other words, commerce was not built to be “native” to the web. But what exactly does that mean?

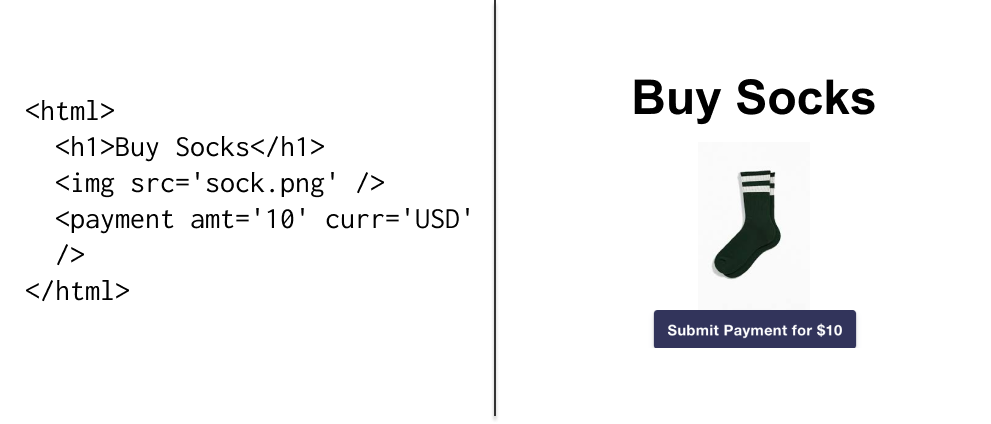

The internet is composed of one thing and one thing only: information. Information is the only thing the internet can understand, that it can convey and distribute. But information is useless unless it can be communicated to people. For that, the internet has HTML. HTML is a markup language composed of different tags that define the types of content that a web page can have. These tags are the building blocks that developers assemble together to build the web.

Now imagine if there were a “payment” tag in the HTML specification. What would that mean? Well for starters, it would be as easy for anyone building a website to incorporate payments as it would be for them to incorporate text:

IETF, the standards body that governs the core internet protocol, would have to define a new protocol for transferring money over the internet to facilitate these payments. The browser, the application that runs the internet protocols specified by bodies like IETF, would be in charge of implementing the payment protocol and delivering it to the end user. Perhaps different payment methods could be chosen to be used by the user, just as browsers let users choose their search engine today.

This is the vision of native money that Andreessen alludes to: easily accessible to developers, built directly into the network, with the implementation handled by the browser not individual applications.

But wait…while Netscape failed to realize that vision, they did incorporate SSL, which allows for encrypted traffic such as payments, into their browser in 1995. Moreover, PayPal was founded in 1998, bringing easy-to-integrate payments into all websites. Surely a delay of a couple years shouldn’t matter much in the grand scheme of things. So why does Andreessen, looking back, view Netscape’s inability to build payments into the browser as such a big deal?

II.

As I am fond of reminding people, the internet dramatically lowers economic friction. It does so first by eliminating distribution costs: it has become so cheap for computers to send and receive bits that once a piece of information is created, it can be sent to anyone who wants it for free. Next, it breaks down the barriers to entry for new suppliers: because the internet is an open protocol, anybody who wants to can build on top of it. This two-pronged process — lowering marginal costs for consumers while also lowering barriers to entry for producers — is the core mechanism that allows internet companies to disrupt other industries.

Over the last twenty years, we’ve gone from print newspaper delivered by truck to Twitter and Facebook aggregating all the world’s news. From linear television to YouTube. From magazines to Instagram. But these transformations were not inevitable — they were contingent on the types of information that were built into the open protocols that define the web:

Money, however, was not built into those protocols. As a result, within financial services, transaction costs and barriers to entry remained high, while innovation and creativity remained low. And this is deeper than just payments. Banking, loaning, investing — everything related to moving money around would have become more accessible to businesses and consumers alike. In the absence of native commerce, internet companies gravitated towards the information-based business model that was accessible to them: advertising. Or as Andreessen puts it,

Because we were unable to build payments into the browser... that is why the internet today, at least in the US, is predominately based around advertising

Native money did not fail from lack of effort. Netscape partnered with Visa, while Microsoft partnered with MasterCard, both setting out to build payments into the browser. Both failed. The regulatory environment was too uncertain, and risk-averse incumbents banks and payment processors were not eager to embrace a new, untested technology.

So instead, PayPal came about, acting as a bridge from the internet to the traditional financial world. With PayPal, money was not a building block for developers that they could be experimented in building new products with new business models. You could accept payments through PayPal, but only within a standard configured way, using existing payment networks. Now that bridge was (and is) incredibly useful and powerful, but it is nonetheless a fraction of the potential of truly native digital money.

III.

It has been 25 years since Netscape’s failure, and the opportunity has grown exponentially larger. eCommerce is now a multi-trillion dollar industry and represents 10% of all of US retail. Improvements in networking and the advent of smartphones have made the web fast, reliable, and ubiquitous. A whole generation of coders, designers, and entrepreneurs have grown up harnessing the capabilities of the internet to build new products and experiences. But people have not given up on the idea of native money. In fact, there are two compelling movements underway right now to correct the internet’s original sin.

First is the rise of so-called “vertical finance.” Over the past decades, many companies have done the hard work of erecting layers of infrastructure on top of the existing financial institutions and regulations to make it feasible for internet companies to build business models and products centered around financial verticals, such as payments or banking. Vertical finance can trace its origins to 2009, with the founding of Stripe, which not only made it easy for anyone to accept payments on the web, but also built an API that allowed developers to code logic around transacting money directly into their apps.

Today Shopify is 47 Billion Dollar company that lets merchants build eCommerce websites, manage inventory, fulfill shipments, and much more — but the majority of their revenue comes from processing payments, facilitated by Stripe’s APIs. Another example of a vertical finance business model is Uber Money. Uber Money offers bank accounts to Uber drivers that facilitates instant payment for their work, while giving Uber another revenue stream. The strategy of vertical finance is clear: carefully comply with the current financial system while utilizing APIs like Stripe to allow you to build financial products within a walled garden.

The second movement also began in 2009, but takes a polar opposite approach to the above strategy. Cryptocurrencies, which began with the publication of the Bitcoin white paper, have exploded into the mainstream following the crypto boom of 2017. Cryptocurrency fans tend to advocate a wholesale abandonment of the existing financial system for a new one built from the ground-up backed by mathematically precise open protocols. Cryptocurrencies are much closer to the original vision of native internet money with their emphasis on open source, zero barriers to entry, and decentralized payment networks. At the same time, they have adopted the daunting — and quite possibly impossible — task of taking on the gigantic, regulatorily-entrenched financial industry.

Which movement will win? I’m not sure. Vertical finance seems like a safe bet, with many proven successes such as Shopify, but the pace at which it can move is still tied to the speed of the underlying financial institutions and regulators. Crypto, on the other hand, can move as fast as it wants, but as seen by the proliferation of scams and fraud in the space, many are discovering that a lot of the red tape of the current system is there for a reason. It is the difference between trying to breach a city’s walls with a regimented army supplied with well-constructed siege towers, or putting your faith in a rag-tag crew of misfits who have assembled a bomb out of duct tape, kerosene, and spit that they promise will take down the walls in one fell swoop

What I do know is that the opportunity in this space enormous, both for enabling new business models and profoundly improving how people interact with their finances. While the last two decades of the information economy have focused on transforming media, the next one will take on the much larger and more impactful task of transforming the entire way we interact with money and the economy. I, for one, can’t wait to see what will happen.

More for more discussion, seem my follow-up post here.

Thanks for reading this week’s edition of E-conomy! If you have any comments, feedback, or thoughts feel hit me up at twitter.com/noah_putnam. I always am down to discuss what you thought of my arguments — especially if you disagree with me 😉. Finally, if you enjoyed this post consider signing up for weekly essays about similar topics.